Images: Above: A B&B at Hogsback, South Africa. Source: aatravel.co.za

Images: Above: A B&B at Hogsback, South Africa. Source: aatravel.co.zaImage 2: Some of the South African nature-based tourism brochures I've collected.

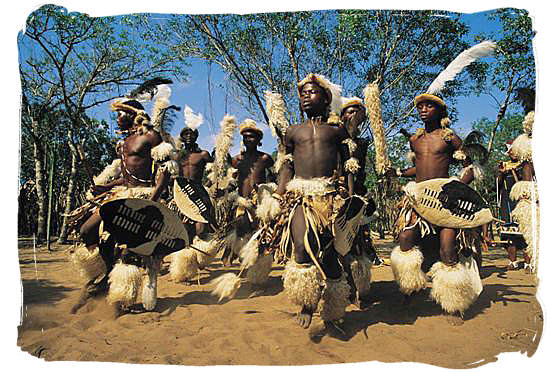

Image 3: Young Zulus performing a traditional Zulu warrior dance. Source: south-africa-tours-and-travel.com

I have long been using this blog to explore the topics of ecotourism and the sublime individually, but have until now put little effort into connecting the two, though the connections are engrained into the very essence of ecotourism. The elements that define the sublime in nature – seclusion, Otherness, vastness, astonishment – are exactly the components that are offered, at least in theory, by ecotourism. This brand of travel offers access to remote, pristine natural places which have not been developed or degraded by the hand of man, accompanied by the promise that they never will meet such a fate. Essentially, it offers the sublime: immense distance from the familiar, physical and mental escape from the complexity and drudgery of everyday life, and the opportunity to experience an ancient, untamed and untamable world. The ecotourist expects experiences rivaling those of Joseph Conrad, Ernest Hemingway, Percy Shelley and other great travel writers: true adventure, filled with the excitement of novelty and discovery. The reality may not be quite as romantic as these expectations, but in theory, this is exactly what ecotourism offers.

Promotional materials for nature tourism and ecotourism draw on gently sublime imagery like that found in historical travel writing, using phrases such as “tranquil mountain surrou

ndings” (Botlierskop Day Safaris), “breathtakingly beautiful” (Aquila Safaris), “unspoilt nature” (Nahoon Estuary Nature Reserve), “largest wilderness on earth” (Schotia Safaris), "unbelievably dramatic view" ("The Edge" Mountain Retreat) and “pilgrimage through time” (Cango Caves). Bhejane Adventures goes further by offering that imagery in the experience itself: “the Knysna forests conjure images from well read stories, of phantom elephants, wood-cutters, Italian settlers and lost travelers.” It goes on to say that the forest “has been off-limits to anybody . . . Bhejane Adventures has obtained the exclusive rights to take small groups of people . . . into the last remaining sections of the Knysna forests.” Martha Honey gave a similar example of the Cruise Company of Greenwich, which advertised “a visit to unknown lands, in this case in one of Costa Rica’s largest national parks: ‘The Corcovado area is so remote, inaccessible, and undisturbed that even most Costa Ricans have never visited.’ The notion that cruise ship passengers will machete their way through Corcovado’s dense, steep, and rain-drenched tropical forest is ludicrous, but the image is appealing” (Who Owns Paradise, 62). The tourist wants to experience something unique, authentic and as far from civilization and modern life as they can get; and in this distance, they have the chance to find that natural sublime that can only exist in such remote areas.

ndings” (Botlierskop Day Safaris), “breathtakingly beautiful” (Aquila Safaris), “unspoilt nature” (Nahoon Estuary Nature Reserve), “largest wilderness on earth” (Schotia Safaris), "unbelievably dramatic view" ("The Edge" Mountain Retreat) and “pilgrimage through time” (Cango Caves). Bhejane Adventures goes further by offering that imagery in the experience itself: “the Knysna forests conjure images from well read stories, of phantom elephants, wood-cutters, Italian settlers and lost travelers.” It goes on to say that the forest “has been off-limits to anybody . . . Bhejane Adventures has obtained the exclusive rights to take small groups of people . . . into the last remaining sections of the Knysna forests.” Martha Honey gave a similar example of the Cruise Company of Greenwich, which advertised “a visit to unknown lands, in this case in one of Costa Rica’s largest national parks: ‘The Corcovado area is so remote, inaccessible, and undisturbed that even most Costa Ricans have never visited.’ The notion that cruise ship passengers will machete their way through Corcovado’s dense, steep, and rain-drenched tropical forest is ludicrous, but the image is appealing” (Who Owns Paradise, 62). The tourist wants to experience something unique, authentic and as far from civilization and modern life as they can get; and in this distance, they have the chance to find that natural sublime that can only exist in such remote areas.Although the advertising for these kinds of tours and experiences are often exaggerated, the conditions of ecotourism do provide an ideal setting for the sublime. Ecotourism requires the preservation of a natural area’s integrity, emphasizing the importance of leaving no impact on the environment. This means that the conditions are kept as pristine as possible, with less visible influence from man, and smaller numbers of people are allowed into vulnerable areas at one time, to minimize their negative impact. This allows the traveler to find greater seclusion and more authentic, unadulterated nature than in other forms

of nature travel. Ecotourism’s inclusion of local culture can also encourage a sense of the sublime Other in the tourist. People are drawn by cultures that are distinctly different from their own, and especially enjoy seeing those that appear to be living pre-modern lifestyles, without modern technology and with a greater connection to nature. Not only does this give them that sense of separation and seclusion from the familiar that can facilitate the sense of the sublime, but it excites Romantic notions about the woes of industrialization and our loss of natural purity, which encouraged the original turn after the Industrial Revolution to the natural and sublime by Romantic poets. Thus cultural preservation becomes profitable to local people, encouraging them to resist Westernization or at least put on displays of traditional culture, which attracts greater tourist attention. When surrounded by a culture that seems rooted in an ancient past and by nature that has resisted any human impact, the tourist is taken far away from the familiar, and with the realization of their separateness and lack of control, and without the distractions of technology and modernity, they have the possibility of experiencing the sublime.

of nature travel. Ecotourism’s inclusion of local culture can also encourage a sense of the sublime Other in the tourist. People are drawn by cultures that are distinctly different from their own, and especially enjoy seeing those that appear to be living pre-modern lifestyles, without modern technology and with a greater connection to nature. Not only does this give them that sense of separation and seclusion from the familiar that can facilitate the sense of the sublime, but it excites Romantic notions about the woes of industrialization and our loss of natural purity, which encouraged the original turn after the Industrial Revolution to the natural and sublime by Romantic poets. Thus cultural preservation becomes profitable to local people, encouraging them to resist Westernization or at least put on displays of traditional culture, which attracts greater tourist attention. When surrounded by a culture that seems rooted in an ancient past and by nature that has resisted any human impact, the tourist is taken far away from the familiar, and with the realization of their separateness and lack of control, and without the distractions of technology and modernity, they have the possibility of experiencing the sublime.

No comments:

Post a Comment